Issue #2: How Noclip is preserving your favorite video game memories

The past, now in HD

This is the second issue of Fan Service: a look at fan communities preserving, remixing, and mythologizing their favorite games.

For seven years now, Danny O’Dwyer and the team at Noclip have been crafting some of the most polished and well researched video game documentaries on the internet. Now, in a video recently released on their YouTube channel, they’ve announced another big project: their journey to digitize thousands of tapes documenting years of video game history — tapes that were soon to be discarded and dumped into a landfill.

Called the Noclip Game History Archive, you can already see some of the fruits of that labor. There is a high quality version of Microsoft’s 2009 press conference, where the infamous Kinect peripheral got a big moment in the spotlight. There’s the Space World 2000 GameCube tech reel, which showcased a battle between Link and Ganondorf rendered in a “realistic” art style that would elude Zelda fans until the release of Twilight Princess in 2006. There’s a tour of an employee only museum at Nintendo’s old American headquarters.

The archives are an important piece of the video game preservation puzzle, no doubt. But there’s also something interesting about the almost uncanny relationship we have, as fans of video games in the early aughts, to these videos. Many of them we watched originally over painfully slow internet connections, our dial-up modems struggling to stream videos rendered at now unthinkably low bitrates. Much of the awe-inspiring graphics we saw by way of the internet in early 2000 were really a mess of colored pixels.

This archive, then, functions almost like a great remastered video game: showing us the thing as we remember it, not as we saw it.

Last week, I spoke with Noclip’s Danny O’Dwyer about what is actually on these tapes, how documentary filmmaking continues to inform his ideas about preservation, and what this archive means for those of us who originally encountered this media on the early-Internet.

✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨

Have you actually counted the tapes? Do you have a ballpark sense of how many there are?

I haven't. And the reason I haven't, is because the mini DV tapes is the problem. In the big DV cam tapes…let’ s say there’s 80 tapes per box? But the mini DV, there could be like 400 tapes in there, because they're tiny. And they're all loose. So it's hard to tell. If I was to ballpark guess, I'd say somewhere between 2000 and 4000 maybe in total.

You’re a documentarian. I imagine constantly searching for B-roll and usable footage is a big part of your life. Did that play a role in wanting to do this work?

Absolutely. I think one of the coolest things about this is seeing footage that either has never been online, or it does exist online, but its this terrible 240p resolution version that we have to like, rip off YouTube and use as B-roll.

There is literally a documentary, that we haven't announced yet, that's about a video game studio that I have found a bunch of footage of them from 15 years ago that's in 1080i. Which is like, awesome! We just got a whole bunch of stuff for free, that we didn't have to go and film or spend a bunch of time doing. You know, it's amazing. So that absolutely helps.

There are people who do video game preservation full time. There are amazing organizations out there, like the Video Game History Foundation, for instance, who are really good at doing this, and its their day to day. In a way, I feel like this fits better with people like us, because all we do is log footage, right? We go out and film a bunch of stuff. We capture gameplay, we film interviews, we film B-roll — then we log all that footage, which means we take notes of what it is, then we get it all in timelines, we organize it, we database it, and I we make something out of it.

So its all the stuff at the start, we're already doing on a day to day. And then we don't have to make anything out of it, we just we just render it. Like maybe we'll tweak it a bit here and there: we can color correct stuff a little bit. We can clean up the audio. Stuff that takes us hardly any time, because we're usually doing like 50 jobs to produce these documentaries at at the pace that we produce them. We don't make a documentary every four years, like a Kickstarter documentary. We make 15 or 20 a year.

I'm really excited for YouTubers to use this stuff in their own edits, and we're definitely going to use it in our own edits. Honestly, there's a couple of games here that have so many interviews that we're like: can we just make a documentary out of these materials alone? Like, we have a bunch on on the first Stalker game. Stalker 2 is coming out later this year. Imagine a doc where the first half is all these retro interviews. And then the second half, especially given the different world Ukraine is in at the moment, is like the modern day, 20 years later, with those same developers and the studios they’re at. There’s so many cool new things that we’re going to make ourselves, and I hope that other creators do that as well.

Are you collaborating with experts outside of Noclip for this?

I have spent a long time talking to people about best practices. I did about four months of research on repairing VCR players, optimizing VCR players, optimizing recording.

But even then, since we uploaded stuff, we had feedback from people. I've had emails from, you know, two dozen people. We've had lots of comments on YouTube saying, “Oh, could you do it this way? Or how about this?” And we've changed our workflow.

We were originally uploading any videos that were 4-3 ratio in a 1080p wrapper, so we could get the best bitrate out of YouTube. But somebody in the comments said, “oh, actually if you use this resolution that is a 4-3 resolution, you'll still get the bitrate.” And it was a new thing that had been added to YouTube in the past two years. So we actually unlisted a bunch of videos, re-uploaded them, and on Archive we replaced the files.

You’re learning as you go.

Yeah and honestly, the VHS tapes are the only real tricky ones, because that's analog. The rest of the videos are digital. So that means, when you're outputting, you’re outputting the lossless digital signal and it's just a case of converting it. You either convert it or you don’t, It's a very binary thing. You either mess up the conversion or you don't.

It’s not like VHS, where there are all these different ways you have to try and keep the signal and retain black levels and do all this sort of stuff…and the VHS collection is not that large. It's only about two boxes.

Two boxes means…how many tapes?

[Laughs.] Like it's only like 140 tapes or something, you know, easy peasy. Most of them are right behind me right here, actually. There's the Oddworld Munchies Odyssey.

One of the things we're going to do on Archive, is a lot of you can actually upload like separate materials to archive, like pictures of them and stuff.

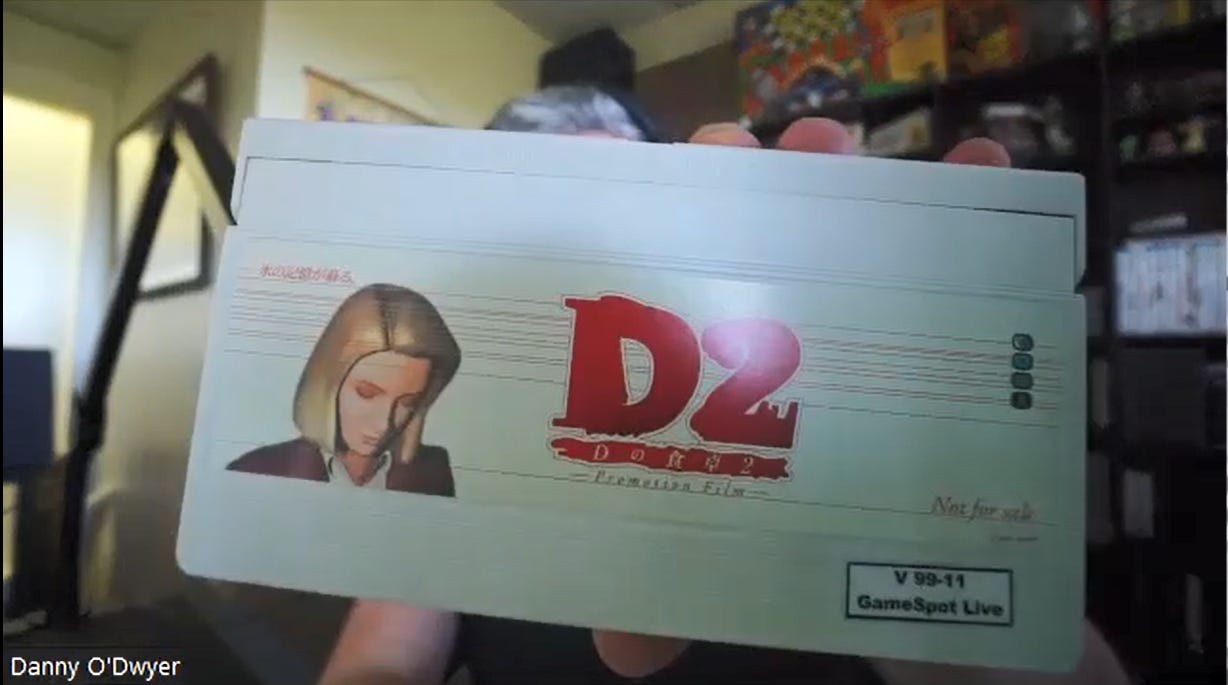

Some of them look really cool.

That is really cool. Some professional labeling on there.

Yeah that’s for D2, an old Dreamcast game.

Here is Anubis, which is Zone of the Enders 2 , TGS trailer. And it's got like it's a white VHS with a Konami label on it.

Are there tapes you haven’t talked about yet, that you’re excited to get in there and digitize?

We have one master VHS tape, which is about about two and a half hours of E3 99 B-roll, so it's kind of the one we don't want to fuck up. So I've done like maybe…five recordings of it, on different settings and different ways to try and have a look. It’s just packed full of trailers from from that era. Some of it's more interesting than others, like a lot of Game Boy Advance trailers.

And then we have some tapes that are faulty, but we’re putting them aside. Like we referred to one in the trailer. We have one [that has] mid-nineties Nintendo B-roll from one of the E3s. And there are organizations that you can send those tapes to who are really good at getting the stuff off of broken tapes.

We have one problematic Konami tape, which recorded fine the first time, and then broke on our second playthrough of it. And that has a bunch of stuff on it like Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater trailers and other things. But it's problematic. So that one is one that we'll get around to rerecording, or I might send away to get recorded just to have it done properly.

I was shocked at how good the Space World footage sounded. Is there other footage that stands out, that once you digitized made you think about it in a different way?

The Space World demo was great because that was a video that has existed online for years, and looks like shit. And people have been trying to like, up-res that one. I fuond an AI upscaled one from six months ago. People are still trying to make that one look good.

And I'm with you. Like the thing that shocked me the most on that footage was how good it sounded. And I don't know if it's because we don't notice the sound being degraded as much, but in general, the sound on on the VHS is really good.

When it comes to like looking at footage and going, “wow” — for me, it's the Mid-aughts HD cam footage. Because all of this stuff was filmed on broadcast quality cameras, but we never saw it that good. There was no 1080p internet video in 2008. You know what I mean? You were lucky if you're getting like 720 max, and mostly were not. Like online video you were getting 480p. And even then, if you were getting 720, it was some terrible codec that just like crushed everything down and made it flat as hell.

So the first time I recorded the Microsoft conference and it was like 1080i — because it is going on a tape and is interlaced — I was blown away. I was like, oh my God. It's like IMAX in comparison to like the crappy versions that that I even remember watching back in the day, like livestreams. So that to me was the coolest thing. And like right now I'm literally recording the Sony press conference from E3 2006 and it looks unbelievable. The stuff looks so much better.

And weirdly, it changes the context. I found a Miyamoto interview earlier today — I’m rendering it at the moment over there — from when the Wii came out, so its like 2006, something like that. And when you watch old videos from that era, they are like, lower frame rate maybe. Or like blurry, or like the aspect ratio is weird, or they have weird graphics on them or whatever it is. And it feels old. But when you watch the raw tapes, or the stuff we’re going to upload which is like, here is the raw interview and for that one we're going to have Miyamoto talking clean, because you can do multiple language, multiple audio tracks on YouTube now. So we'll have like the Japanese, just him talking. And then we'll have the one that's dubbed as well. And when you look at it on these tapes: it feels like it was just filmed yesterday. It feels like closer in time or something. And I think that's like super interesting. Like that to me is the the part that is crazy is like…this stuff looks better than it looked back then. So it feels newer in a way than it actually is, which is fascinating…

…the other thing as well, because video was expensive for especially video game websites…they had to be really economical. So you know, we have found tapes that are just packed full of interviews, and they might have only ever used 4 minutes of the interviews. But actually they asked them loads and loads of questions about all this detail about the game or whatever.

We put up footage from a tour of Nintendo's office in Redmond. And it's really funny reading the comments because people are like: “what is this cameraman doing?” He’s doing all these zooms, and focus pulls — he knows that there's only going to be like 20 seconds of this tour is going to be shown on a video, because they have to make a five minute video about this thing. So it's all just b-roll, he’s just getting B-roll, B-roll, B-roll. So it's very funny to like put a whole video of that up, because we can now. We can put up in 1080 60, 1080p, and we can now, because video is free now because of YouTube. And that’s cool. I mean that's the thing that I'm so excited about this is, that like we're putting up stuff that was never online, and never would have been online if we hadn't sort of intervened.

What do you hope is the lasting impact of this archive?

I think I wanted to shock people, so that we don't run into these problems again. And that's hard to to do. But it's part of the reason why we made such a song and dance about this archive, and how close to being thrown out it was. The best time to preserve something is immediately, when you've made it. We're very serious about that here, with the backups we have a you know, interviews and B-roll and gameplay and all that sort of stuff. And so that's the first thing. I just hope that it does that.

And then secondarily, one of the reasons we started Noclip was because there was this gap between what gamers thought about game development, and what the reality of game development was. And I think especially in the era we're talking about here, like the early aughts to the, you know, 2015 or whatever to 2012, I think there was even less of a human connection to game development then than there is now…back then, often times you never even talk to a developer. You talk to a PR person who was representing the company and their interests, and the interests of the business side as much as anything else.

And so what I hope is that through these tapes, we can actually humanize the past as well. The Miyamoto interview is a really good example. That Miyamoto interview would have been, you know, just the style of the time. It would have been edited into into a package. It would have had a fancy graphic at the start, and a lower third pops up: Shigeru Miyamoto! And then he'll be talking and there's music playing underneath it. And then B-roll of the game. Video back then was packaged as this very like MTV Popcorn like thing. It wasn't very earnest and slow. And because of that, it sort of added to this barrier that existed, but added to the idea that games were products, and products alone. And Miyamoto is just a guy. Who's, like, really smart, but also right place, right time or whatever. And so I think like… [we’re] putting them up with that context.

We know loads about contextualizing footage, because that's documentary. Documentary filmmaking is basically like picking what truth that you want to tell. And then you bend the truth, and you warp it in a way that…is hopefully speaking to a larger truth.

So we understand like, oh, if you strip a lot of these things away from the video, then actually it humanizes it a lot more. So by putting this stuff up in this format, I think it actually will hopefully recontextualize the past with people maybe a little bit more.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

If you want to share a project with me or talk to me about this newsletter, email me at vracovino at gmail.com.